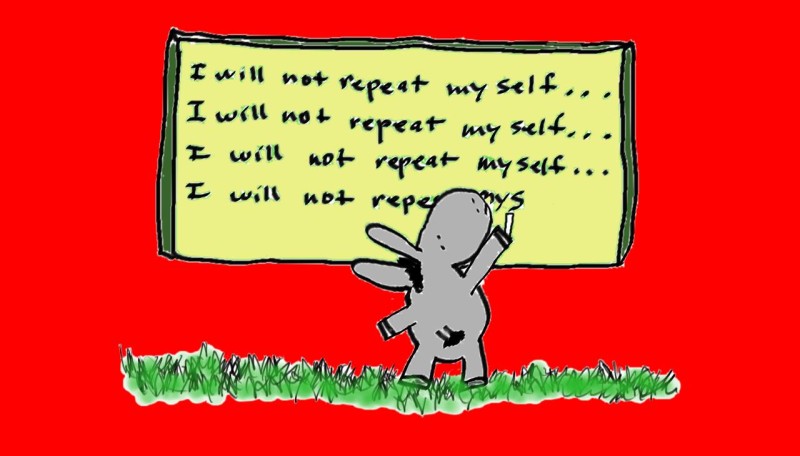

They seem to be repeating themselves, thought Blurtso, listening to the things they were saying. They seem to be repeating themselves. I’m glad I don’t do that. Because they seem to be repeating themselves.

Category: Harvard

“Blurtso sings the donkey electric”

“Blurtso sings the donkey electric”

I sing the donkey electric!

A song of asses I sing, near and far!

Asses on hills, asses in fields, asses in herds,

more bountiful than the once-bountiful buffalo,

asses on land and asses at sea, asses short, skinny, fat and tall!

Multitudes of asses, spanning these star-spangled states!

I have perceived that to be an ass

is to be enough.

The ears of the ass are sacred, delicate,

twitching receptacles of sound,

assiduous antennae registering, recording all,

the hooves of the ass are no less

than the slippers of sultans

striding silken alfombras and seraglio stone,

the snout of the ass and his nostrils—a dual lamp

of Aladdin—inhaling flowery fragrance,

leading to wished-for fiestas of pumpkin pleasure,

the ass’s tail, though stumpy or small, and swatting flies,

is a palm fanning reclining Cleopatra,

his teeth, precious jade, are greened and polished

by the grass of a thousand fields,

his attentive eyes and friendly balance of features,

—courtly countenance and caryatid composure—

no less perfect than the visage of Helen.

Such asses I see, to the north and to the south!

From blistering bivouacs of winter

to blazing battalions of summer,

Patagonia to Peloponnese, Malibu to Manhattan,

Concord to Cambridge, every here

and every there, asses I see! Brown, grey,

yellow, red, purple, orange, azure asses!

Asses in other climes, asses in other times,

French, British, Australian, Arabian, Asian asses!

Eating every blade of grass, an ass!

Trampling every leaf that falls, a hoof!

Wading every stream that sings,

a snout, a snort, and a bray!

Hee-haw goes the jack!

Hee-haw goes the jenny!

Hee-haw go the judge and jury and judged!

Hee-haw from the dell! Hee-haw from the glen!

Hee-haw at mid-day! Hee-haw at the moon!

I see the resigned ass, bearing a load,

obeying the coax of his lord,

I see the boisterous ass braying,

in the barn, his bonny bray,

I see the amorous ass (of these there are many),

expressing exigencies by day and by night,

I see farms, fields, freeways and burgs,

each in their way, replete with asininities,

I see the asinine politician, professor, and poet,

each one leaving a brand on the asses of asses.

And the asses of yore, you ask, where are they

with their clip and clop on the stones of the street?

Les ânes voici! I say! Les ânes voici!

Heeding the whinny and neigh,

and ass-bray of the future!

What song do I sing? (you ask and I reply),

I sing the song of asses!

Certain, and stoic, and strong!

From each face an ass!

From each office, family, and farm!

Asses I sing! Avalanches of asses!

I sing! I sing a song of asses!

I sing the donkey electric!

“Weohryant University” (XXII) – What 101

The question for today’s class, said Blurtso, is: “What is the difference between sympathy and empathy?”

Sympathy and empathy? said Morton.

“Sympathy,” said Glouster, “is a relationship between persons or things wherein whatever affects one similarly affects the other.”

And empathy? said Chelsea.

“Empathy,” said Glouster, “is the capacity for experiencing as one’s own the feelings of another.”

That sounds like the same thing, said Frank.

Both words, said Glouster, come from the Greek word, “pathos,” meaning, “suffering, emotion, passion.” In Greek “sym” means “with” and “em” means “in.” So sympathy is “suffering with” another, while empathy is “suffering in” another.

I still don’t understand, said Morton.

Isn’t that the same as compassion? said Emma Lou.

“Compassion,” said Glouster, is “sorrow or pity aroused by the suffering of another.” It is derived from the Latin words “com” or “with” and “passion” or “suffering.”

So “compassion,” said Emma Lou, is the Latin equivalent of the Greek word “sympathy.”

Exactly, said Glouster.

That still doesn’t tell me, said Morton, the difference between sympathy and empathy.

Both words, said Glouster, imply a relationship, or “oneness” between the subject and object, between the “sympathizer” and the other.

Just like in the Upanishads, said Emma Lou, and the Tao Te Ching. Both books talk about the oneness of all things, that separation is just an illusion.

The gospel of Matthew, said Glouster, says “love your enemies.”

Does it say you and your enemies are one? said Emma Lou.

Not exactly, said Glouster, but it goes on to say, “I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

That’s pretty much the same thing, said Chelsea.

The gospel of John, said Glouster, says, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Isn’t that compassion? said Chelsea.

“Compassion,” said Emma Lou, is feeling someone else’s pain as your own. The way to do that is not to see others as separate from you.

One hundred fourteen of the one hundred fifteen verses of the Quran, said Frank, begin with “In the name of Allah the compassionate, the merciful…”

Ommmm, said moose.

What? said Glouster.

I think he said “Ommmm,” said Frank.

Ommmm (phonetically “aum”), said Emma Lou, is from the Upanishads, it is the monosyllable which contains all syllables and all sounds. It represents the oneness underlying multiplicity—the non-duality of “Brahman” beneath the dualism and illusion of “Maya.”

The illusion of Maya? said Morton.

The illusion that we are not all one, said Emma Lou.

So compassion, said Frank, is recognizing—beyond the illusion of separation—that we are all one?

Exactly, said Emma Lou.

I still don’t understand, said Morton, the difference between sympathy and empathy.

Think of it this way, said Glouster. When someone is suffering because of a specific situation, but you have not experienced that situation yourself, you can only sympathize with them, but if you have experienced that same situation, you can empathize.

That’s very confusing, said Chelsea.

Yes, said Morton, I feel exactly the same way.

“Blurtso tries his hoof at cubism”

“Weohryant University” (XXI)

“Weohryant University” (XX)

Do you think we’re early? said Morton.

I don’t want to appear anxious, said Emma Lou.

Neither do I, said Chelsea.

How long should we wait? said Morton.

Until it’s time, said Emma Lou.

How will we know? said Morton.

They’ll tell us, said Emma Lou.

What if they don’t? said Morton.

Then we’ll never know, said Chelsea.

They’ll tell us, said Emma Lou, if they want us to know.

And if they don’t? said Morton.

Then they won’t tell us, said Emma Lou.

That makes sense, said Chelsea.

Where are the others? said Morton.

They’re waiting for us to decide, said Chelsea.

They don’t want to appear anxious, said Emma Lou.

What’s wrong with appearing anxious? said Morton.

It makes you look greedy, said Emma Lou.

Even if you’re willing to share? said Morton.

Maybe they want us to wait, said Chelsea.

Why? said Morton.

Because anticipation increases desire, said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Chelsea, like in the Kama Sutra.

The Kama Sutra? said Morton.

The Kama Sutra, said Chelsea, is one of the books on our reading list.

The one the moose keeps hogging? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, but I managed to sneak a peak.

What does it say? said Morton.

It says that withholding pleasure increases desire, and increasing desire increases pleasure.

What if you don’t get what you desire? said Morton.

Then you still get the pleasure of anticipating, said Chelsea.

The pleasure of anticipating? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, like when you spend the winter anticipating the spring fashions, and when the fashions come out, you’re a little disappointed, but at least you had the pleasure of anticipating them.

That happens for me, said Emma Lou, every season of the year.

But sometimes when you get something, said Morton, it’s as good as what you had hoped for.

That’s true, said Chelsea, but getting it doesn’t diminish the pleasure you got from anticipating it.

It teaches you, said Emma Lou, to enjoy the journey and not focus on the destination.

The destination? said Morton.

The object of desire, said Emma Lou.

We’ve waited long enough, said Morton.

You may be right, said Emma Lou.

I wonder if the others are enjoying the wait? said Chelsea.

Birds can be very patient, said Emma Lou.

That’s true, said Morton, I watched Frank sit on a fence for five hours yesterday.

You watched him for five hours? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Morton.

And you didn’t get impatient? said Chelsea.

No, said Morton, I didn’t want to eat him.

So you’re only impatient, said Emma Lou, with things you want to consume?

Yes, said Morton.

What if you’re not hungry? said Emma Lou.

There are some things I want to consume, said Morton, whether I’m hungry or not.

That’s not very healthy, said Emma Lou.

I know, said Morton.

Do you smell that? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, I do.

It must be time, said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, it must be time.

Really? said Morton, I was just starting to enjoy the anticipation.

“Blurtso visits his friends on Walden Pond”

Hello, said Pablo and Bonny. Hello, said Blurtso. What are you doing? We’re taking veggies to our cabin, said Pablo. How about you? I’m going to class, said Blurtso. Really? said Bonny. Why don’t you come visit when you’re done? Ditto would love to see you. Ditto? said Blurtso. Ditto is Bonny’s stuffed animal, said Pablo. Oh, said Blurtso. But he’s remarkably intelligent, said Bonny. I’m sure he is, said Blurtso. So you’ll come? said Bonny. I don’t think so, said Blurtso, I’ve got an exam tomorrow. That’s too bad, said Pablo, we could go for a swim. With the ducks? said Blurtso. Of course, said Pablo. Hmm, said Blurtso, do you know anything about the underlying causes of World War One? No, said Pablo, but I’m sure we can figure it out. Great! said Blurtso. I’ll see you after class.

No one’s home… except for Bonny’s stuffed animal. He sure is funny-looking. Rabbit-sized ears, boxing-glove nose, two eyes that may as well be one. I wonder what he’s supposed to be? His hooves are wrong for a rabbit… and his nose is wrong for a rhino… maybe he’s a camel or a mouse… or an overstuffed rat… I wonder if he can swim… maybe he’s a sea creature who’s stranded on land… or a land creature who yearns for the sea… Hah! He sure looks funny! But even so… he’s really quite handsome.

I see, said Blurtso. So it was the result of a series of diplomatic clashes over European and colonial issues that stemmed from the changing balance of power after 1867. Exactly, said Pablo.

“Weohryant University” (XIX) – Where 101

Today’s question, said Harlan, is: “Where did it go?”

Where did what go? said Chelsea.

It was here just a minute ago, said Morton.

I didn’t take it, said Emma Lou.

Neither did I, said Frank.

Do you mean “ubi sunt”? said Glouster.

Ubi sunt? said Morton.

“Ubi sunt,” said Glouster, is Latin for “Where are they?” It comes from a Latin poem that begins, “Ubi sunt qui ante nos in mundo fuere?” which translates: “Where are they who, before us, existed in the world?” It was a common theme in medieval poetry, and was most famously expressed by the French poet, François Villon who asked, “Où sont les neiges d’antan?” or “Where are the snows of yesteryear?”

The snows of yesteryear? said Morton.

I don’t like snow, said Chelsea.

Neither do I, said Frank.

I don’t mind it, said Emma Lou, so long as I’m not far from my den.

Why would anyone worry about last year’s snow? said Morton.

It’s a metaphor, said Glouster, for all the things you’ve lost in your life.

Lost? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Glouster, the things you had in the past that you no longer have.

The things I’ve eaten? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, and the friends you’ve lost, and your lost youth.

My lost youth? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Glouster.

I’m not going to lose my youth, said Chelsea.

Of course you are, said Glouster.

Really? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Glouster.

In that case, said Chelsea, I don’t like “ubi sunt.”

Crows live forever, said Frank.

They do? said Morton.

Sure, said Frank, crows, or “ravens”, and nightingales, and even some other birds.

Are you sure? said Morton.

Yes, said Frank, just ask Edgar Allen Poe and John Keats.

Who are they? said Chelsea.

They are poets, said Frank, who wrote about birds who live forever, birds who travel from heaven to earth to hell and then back again.

Have you been to heaven and hell? said Chelsea.

No, said Frank, not yet.

I don’t want to go to hell, said Morton.

Heaven and hell, said Glouster, are metaphors for, “the realm of the dead.”

I don’t want to go there either, said Morton.

Maybe, said Chelsea, that’s where the “ubi sunts” are.

I know a song, said Frank, about “ubi sunt.”

What’s it called? said Chelsea.

It’s called “The Ashgrove,” said Frank, and it has a blackbird in it.

How does it go? said Chelsea.

I don’t remember all the words, said Frank, but it’s about a woman who loses her lover and looks for him in an ashgrove.

Does she find him? said Chelsea.

No, said Frank, he’s buried beneath the green turf.

Is that a metaphor for “the realm of the dead”? said Morton.

Yes, said Frank.

Why doesn’t the blackbird, said Chelsea, fly to the realm of the dead, talk to the dead lover, then return and talk to the woman so she can have a sense of closure?

That’s a good question, said Frank.

What’s closure? said Morton.

Closure, said Chelsea, is talking with your ex-lover until you have nothing more to say.

Why would you want to do that? said Morton.

Because, said Chelsea, if you say everything you have to say, you can stop thinking about him when he’s gone.

So he doesn’t become an “ubi sunt”? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea.

I would like to be an “ubi sunt”, said Emma Lou.

So would I, said Glouster.

Why? said Chelsea.

Because, said Glouster, I don’t want to be forgotten.

Being forgotten, said Emma Lou, would be like a second death.

Maybe it’s a good thing, said Morton, for people to go around asking “ubi sunt?”

Why? said Chelsea.

Because, said Morton, it keeps the dead from dying.