Today’s question, said Harlan, is: “Where’s the door?”

The door? said Morton.

What door? said Frank.

There are lots of doors, said Chelsea.

You can’t swing a cat, said Frank, without hitting a door.

Maybe it’s a symbolic door, said Glouster.

An entrance door or an exit door? said Emma Lou.

Why do we want to find it? said Chelsea.

So we can get out, said Morton.

What if there’s no exit? said Frank.

Then we’ll have to stay here, said Morton, until we find it.

Or find an entrance, said Emma Lou.

An entrance? said Morton.

Yes, said Emma Lou, if we can’t get out, maybe we can get in.

Why do we want to go anywhere? said Morton.

That’s a good question, said Glouster.

To see what’s on the other side, said Chelsea.

The other side? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, whenever I see a door, I wonder what’s on the other side.

Even when it says “do not enter”? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, especially then.

Curiosity killed the cat, said Frank.

It did? said Morton.

If that’s true, said Chelsea, why arent’ there dead cats everywhere?

It’s an idiom, said Glouster.

An idiom? said Morton.

An idiom, said Glouster, is “a set expression of two or more words that means something other than the literal meaning of the individual words.”

Idioms, said Emma Lou, often have a basis in reality.

That’s true, said Frank, like the idiom, “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.”

Why would anyone want to skin a cat? said Morton.

It means, said Glouster, “There’s more than one way to do something.”

Or, “Who let the cat out of the bag,” said Frank.

Why would anyone put a cat in a bag? said Chelsea.

Lots of reasons, said Frank.

Like what? said Chelsea.

To stop cats, said Frank, from chasing birds.

Oh, said Chelsea.

I suppose birds aren’t fond of cats, said Morton.

No, said Frank.

What animals do donkeys dislike? said Emma Lou.

We like all animals, said Chelsea.

Except dogs, said Morton, when they’re nipping and yapping at your heels.

That’s true, said Chelsea, but some dogs are nice.

I don’t like crocodiles and alligators, said Glouster, they remind me of U-boats.

What’s a U-boat? said Chelsea.

A U-boat, said Glouster, is a submarine. The name comes from the anglicized version of the German word, “U-boot,” which comes from the word “Unterseeboot,” which means “under sea boat.” In World War II German U-boats plundered U.S. and Canadian merchant ships carrying supplies to allies in Western Europe.

I hate war, said Chelsea.

How does a submarine go under the sea, said Morton, without water leaking through the doors.

The doors, said Glouster, are air-tight. Nothing can get in or out.

There’s no exit? said Frank.

Not as long as the U-boat is underwater, said Glouster.

I don’t like to be trapped in closed spaces, said Frank.

Nor do I, said Glouster.

I don’t mind, said Emma Lou, as long as I can dig my way out.

“When one door closes,” said Glouster, “another one opens.”

Is that true? said Morton.

It’s an idiom, said Glouster, that means “When one opportunity is lost, another one presents itself.”

I’ve been in a barn, said Morton, that had two doors which were both closed.

What did you do? said Frank.

I stopped thinking about getting out, said Morton, and started thinking about something else.

You opened a door in your mind, said Emma Lou.

That’s right, said Morton.

Maybe that’s the door we should be looking for, said Frank.

The door in our mind? said Morton.

Yes, said Emma Lou, the door to imagination, to new perspectives, possibilities, and opinions.

I use that door all the time, said Chelsea.

It’s a very nice door, said Morton.

And it’s almost always open, said Emma Lou.

Almost? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, sometimes it’s closed by habits and prejudices we’ve adopted from those around us.

A Scottish journalist named Charles Mackay, said Glouster, wrote a book called, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

What’s it about? said Chelsea.

It’s a book about crowd psychology, said Glouster, and how individual delusion can become mass delusion.

Mass delusion, said Emma Lou, is called “reality.”

How can you tell, said Morton, if what you believe is a delusion?

That’s a good question, said Chelsea.

What’s the answer? said Frank.

I don’t know, said Morton, maybe that’s the door we should be looking for.

Tag: photos

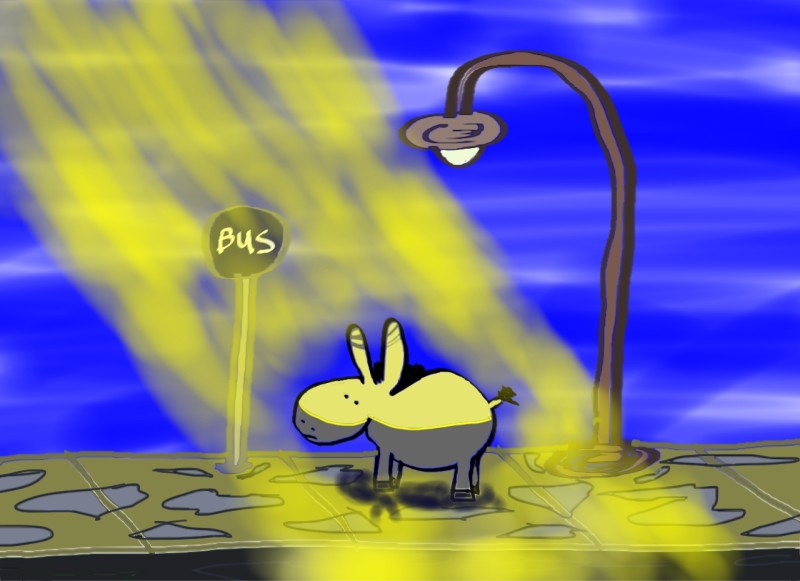

“Blurtso gets caught in the rain”

Hmm… it’s starting to rain. I wonder if I should go into a shop. If I do I’ll probably miss my bus, and then I’ll have to wait for the next one. And if it keeps raining I’ll miss that one and have to wait for the next one, and the next one… hmm… and then it’ll get dark, and the shop will close, and they’ll throw me out after the last bus leaves, and I’ll have to spend the night in the rain, and in the dark… hmm… unless I hitch-hike, but no one will stop for a wet donkey, not with a new car, unless someone does, someone with an old car that smells worse than a wet donkey… hmm… or someone who doesn’t bathe, or has bad intentions, or has a rifle, or owns a forced-labor copper mine… and I’ll be donkey-napped and flown to the mine on a private jet smuggling contraband, and military secrets, and I’ll be forced to work in the mine day and night, living on coca leaves and betel nut… hmm… knowing that the future of the world lays in my hooves if I can only escape and steal back the secrets, and I’ll have to bribe the guards, or sneak away while they’re smoking, and slip into the hills and build a raft, and sail it to the sea where I’ll board a steamer… hmm… and I’ll cross the Atlantic, until the ship hits an ice burg and sinks, and I’ll climb into a lifeboat which I’ll sail through the wreckage pulling out survivors… hmm… and they’ll all be grateful, all except one, the one who is a guard from the mine and has been following me, and is going to kill me the minute we reach Greenland…

Hey… it stopped raining.

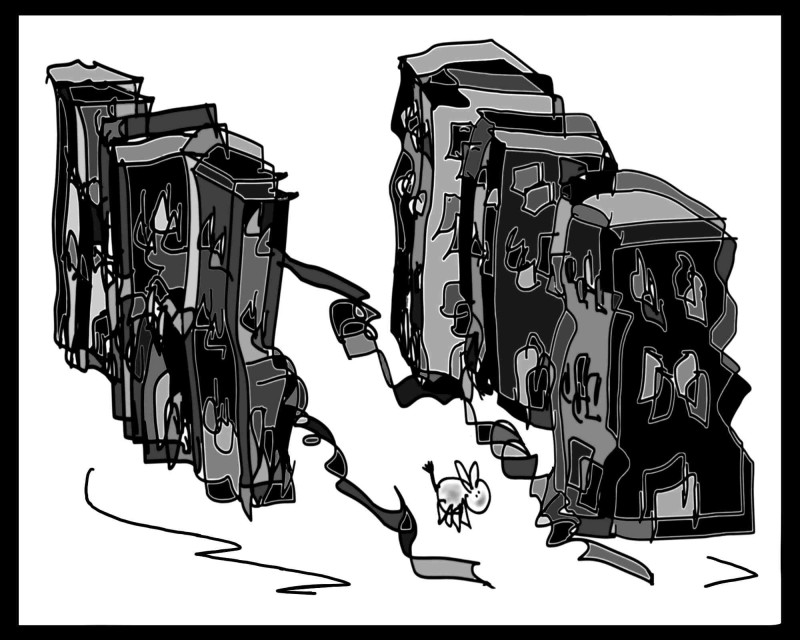

“Blurtso dreams in black and white”

“Blurtso plays a quick round of golf”

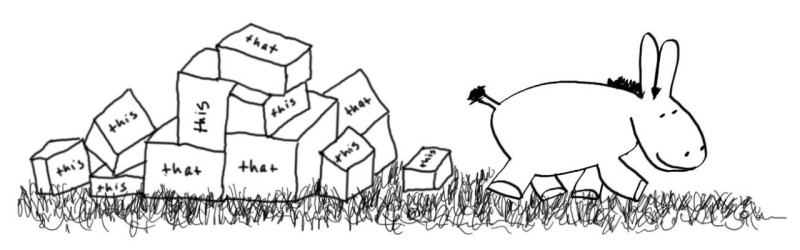

“Blurtso lets go”

Let me see, said Blurtso, I can let go of this and that, and I can let go of that and this. Yes, that’s better said Blurtso, feeling better already. And I’ll let go of that and that and that, and I’ll let go of this and this and this. And of course, I’ll let go of letting go, he said, feeling as good as he had ever felt.

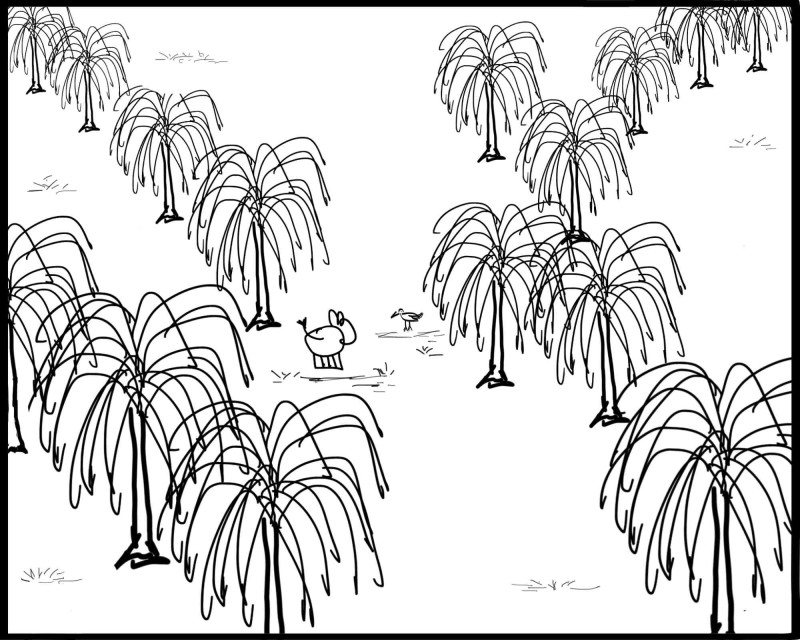

“Blurtso finds a marble”

What’s this? said Blurtso, pawing up a marble. Wow… an aggie! and here’s another… an opal, and a cat’s eye, and an oxblood, a turtle, a ruby, and a steely! Let’s play keepsies! he said, scattering the ducks in a circle he drew on the ground. If I could just knuckle down, he thought, pressing his hoof into the sand. O.k., here goes… bull’s eye! he said when his taw knocked a duck off the pond. Now I’ll go for that granddaddy… bingo! Now I’ll get that peawee… bang! Blurtso continued to shoot, striking one duck after another until the circle was clear. Hmmm, he said, feeling as empty as the empty circle, maybe I shouldn’t have won all the marbles.

“Weohryant University” (XV) – What 101

Today’s question, said Blurtso, is: “What is that blur of movement?”

I don’t see anything, said Morton.

Neither do I, said Chelsea.

Maybe it’s moving too fast to be seen, said Frank.

I suppose it could be anything, said Morton.

Anything, said Chelsea, that’s moving too fast to be seen.

If it’s moving too fast to be seen, said Emma Lou, how do we know it’s really here?

I suppose we don’t, said Frank.

Maybe we should make a list, said Glouster, of the things that move fast.

I can move fast, said Frank, when I’m hunting or being hunted.

So fast, said Chelsea, that you can’t be seen?

I don’t know, said Frank, I don’t have a mirror.

The next time you’re being hunted, said Chelsea, tell me so I can see if you can be seen.

Humming birds move fast, said Morton.

So fast, said Chelsea, that they can’t be seen?

Yes, said Morton, if you’re not paying attention.

Is it really possible, said Chelsea, for something to move too fast to be seen?

At the subatomic level, said Emma Lou.

That’s because it’s small, said Glouster, not because it’s fast.

It’s both, said Emma Lou.

First we can’t trust our sense of smell, said Morton, and now we can’t trust our sense of sight?

If things can move too fast to be seen, said Chelsea, how do we know we’re not surrounded by things moving too fast to be seen?

I think everything moves too fast, said Morton. Why can’t we all slow down?

That’s a good question, said Emma Lou.

Humans move fast, said Frank.

Yes, said Emma Lou, they’re always in a hurry to get somewhere.

Where do you think they’re going? said Chelsea.

They hurry to work, said Glouster, then hurry to finish, then hurry home, then hurry to go out, then hurry to return.

If something, said Morton, is moving too fast to be seen, is it moving too fast to see?

That’s another good question, said Emma Lou.

People in a hurry can’t see me, said Chelsea.

And the joggers along the Charles, said Glouster, don’t see me.

My cousin, said Frank, was hit by a person who didn’t see him.

I’m sorry, said Chelsea.

What’s the fastest thing in the world? said Morton.

Light is the fastest, said Glouster.

How fast? said Morton.

186,000 miles per second, said Glouster.

That’s fast! said Morton.

So fast, said Glouster, that time stands still.

What? said Morton.

When an object, said Glouster, moves at the speed of light, time stands still for that object.

Who says? said Morton.

Einstein says, said Glouster

The bagel maker? said Morton.

No, said Glouster, the physicist.

So if I moved at the speed of light, said Morton, I’d have all the time in the world?

You’d be immortal, said Emma Lou.

That would be great! said Morton.

Jorge Luis Borges, said Glouster, wrote a story called, “The Immortals.”

What’s it about? said Chelsea.

It’s about a man, said Glouster, who finds the fountain of immortality, takes a drink, and becomes immortal.

Does he move at the speed of light? said Morton.

No, said Glouster, he just lives forever.

Ravens are immortal, said Frank.

They are? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Frank, we can travel from the world of the living to the world of the dead, and back again.

Are you immortal? asked Chelsea.

I will be, said Frank, in the future.

If you could travel at the speed of light, said Morton, you wouldn’t have any future.

What happens to the man in “The Immortals”? said Emma Lou.

He lives for thousands and thousands of years, said Glouster, and learns every language, and reads every book, and does everything again and again and again, until he finally decides to look for the fountain of death.

Of death? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, because immortality is unbearable.

That’s very interesting, said Emma Lou.

It makes you feel sorry for the gods, said Chelsea.

It makes heaven sound less attractive, said Emma Lou.

Maybe moving at the speed of light, said Morton, isn’t so good—you wouldn’t have a future and you wouldn’t have a past, you couldn’t be seen and you couldn’t see.

So death is a good thing? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, it is.

But I don’t want to die, said Chelsea.

Even after you’ve done everything again and again? said Emma Lou.

I haven’t done everything again and again, said Chelsea.

It would be like a “deep and dreamless sleep,” said Morton.

A what? said Chelsea

That’s what the Upanishads say, said Morton.

Are you reading the Upanishads now? said Chelsea. I’m still in the Mahabharata. There’s a war and everyone is fighting for life and death.

I suppose the possibility of death, said Emma Lou, makes life more exciting.

I’m never more alive, said Frank, than when I’m hunting or being hunted.

I still don’t know how, said Morton, moving fast makes time stand still.

I think people move fast, said Chelsea, so that they will have more time.

Time to do what? said Emma Lou.

Time to move faster, said Chelsea, until time stops and they become immortal.

Which is the same as being dead? said Morton.

We’re back to where we started, said Glouster.

I suppose we’ve been moving so fast, said Morton, that we haven’t gone anywhere at all.

“Weohryant University” (XIV)

“Blurtso gets an A on his first assignment”

“Weohryant University” (XIII) – Where 101

Welcome, said Harlan, to “Where-101.” Today’s question is: “Where is Borneo?”

What is Borneo? said Morton.

No, said Harlan, “Where is Borneo?”

In Asia, said Glouster.

What’s he doing in Asia? said Morton.

Borneo isn’t a he, said Glouster, it’s an it.

An it? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, an island north of Java.

I like a cup of Java in the morning, said Frank, sometimes two.

Java is an island, said Glouster.

How do you know so much? said Chelsea.

North Borneo, said Glouster, was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1881 to 1941, and a Crown Colony from 1946 to 1963.

Do they speak English in Borneo? said Emma Lou.

The official language is Bahasa Melayu, said Glouster, but English is common, as well as the indigenous languages, Oma Lung and Uma Kulit.

Is Asia far from Boston? said Chelsea.

It’s on the other side of the world, said Glouster.

How far is that? said Chelsea.

Nine thousand two hundred and fifty-two miles, said Glouster.

Wow, said Chelsea, that would take forever!

How fast can you walk? Morton.

Four miles per hour, said Chelsea.

Really? said Morton. I only walk three.

I can fly thirty miles per hour, said Frank.

I wish I could fly, said Chelsea.

I can only walk one mile per hour, said Emma Lou.

I can fly more than forty miles per hour, said Glouster, and swim almost twice as fast.

Wow, said Chelsea, like the speed of light!

Not that fast, said Emma Lou.

Why would anyone live in Borneo, said Morton, if it’s so far from Boston?

Why would anyone live in Boston, said Emma Lou, if it’s so far from Borneo?

What does it feel like to fly? said Chelsea.

It’s like swimming, said Glouster, but in the air.

What does it feel like to swim? said Chelsea.

It’s like flying, said Glouster, but in water.

I don’t swim very fast, said Emma Lou, but I float.

Really? said Chelsea. Without sinking?

Yes, said Emma Lou.

Wow, said Chelsea.

Are there donkeys in Borneo? said Morton.

A few, said Glouster, but there are more elephants.

How many more? said Morton.

Fewer than there were, said Glouster, before their habitat was destroyed.

Is that why you left Borneo? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

That’s very sad, said Chelsea.

Does your family still live there? said Emma Lou.

My brothers, said Harlan, were killed for their tusks.

What?! said Chelsea.

And I don’t know, said Harlan, where my parents are.

I think, said Chelsea, that I’m going to cry.

I’m glad I don’t live in Borneo, said Morton.

It’s a very beautiful place, said Harlan, despite the problems.

Where are your tusks? asked Emma Lou.

I had them removed, said Harlan, so no one would kill me.

Is Asia near India? said Chelsea.

India is in Asia, said Harlan.

Really? said Chelsea. Have you read the Mahabharata?

Yes, said Harlan.

Are you a Hindu? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

Do you believe in reincarnation? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

In the Mahabharata, said Chelsea, the god Krishna tells Arjuna all about reincarnation and selfless service.

That part of the novel, said Harlan, is called the “Bhagavad Gita.”

I think there’s an inherent contradiction in the concept of reincarnation and the concept of Atman, said Emma Lou.

A contradiction? said Harlan.

Yes, said Emma Lou. As I understand it, Atman is the universal Brahman as manifested in the individual. Atman is beyond duality—beyond time and space, beyond good and evil, and beyond ego. And being beyond ego it is beyond individuality; it is the undifferentiated “one” that underlies all things. The concept of karma and reincarnation, on the other hand, says that when a person dies the soul returns to become Atman (the undifferentiated “one”), yet this soul somehow retains the karma (unresolved issues) of the individual when that person was living. This soul, with its unresolved issues, must then be reincarnated in the world in order to work through those issues. My question is this: How can the soul, after the death of the individual, become ego-less Atman and yet hang on to the issues of the ego-individual? If the soul becomes “ego-less” after death, it cannot hang on to the unresolved issues of a former ego. Atman and Brahman, by definition, are beyond maya and unresolved issues.

That’s a good question, said Harlan.

What’s the answer? said Emma Lou.

The doctrine of reincarnation, said Harlan, belongs to the apara vidya—or “lower knowledge”—that operates in the world of “maya” or illusion. The Para Vidya—or “Higher Knowledge”—removes the illusion of the manifold world and, with it, the illusion of the individual soul and its birth, death and hereafter. The function of organized religion is twofold. On one hand it teaches the secrets of wonder and mystery, and on the other it is a rule book for a functioning society. For those with Para Vidya, those who can truly understand the “oneness” of all things, there is no need for the concept of reincarnation, because there are no unresolved issues in “oneness.” For those who cannot embrace or “experience” the mystical union that is beyond individual objects, karma and reincarnation play a civilizing role. They inspire members of society to perform “good” rather than “evil” deeds. They function the same way as heaven and hell in the Biblical tradition—the “carrot and stick” that encourage individuals to behave in a civilized manner without acting like barbarians and killing each other.

Do you, said Emma Lou, have “Higher Knowledge” and embrace the mystical union beyond individual objects?

Yes, said Harlan, I believe I do.

Then why do you believe in reincarnation?

I believe in reincarnation, said Harlan, as a civilizing force for those who remain tied to the illusion of individual objects. I don’t not believe in reincarnation for myself.