What’s this? said Blurtso, pawing up a marble. Wow… an aggie! and here’s another… an opal, and a cat’s eye, and an oxblood, a turtle, a ruby, and a steely! Let’s play keepsies! he said, scattering the ducks in a circle he drew on the ground. If I could just knuckle down, he thought, pressing his hoof into the sand. O.k., here goes… bull’s eye! he said when his taw knocked a duck off the pond. Now I’ll go for that granddaddy… bingo! Now I’ll get that peawee… bang! Blurtso continued to shoot, striking one duck after another until the circle was clear. Hmmm, he said, feeling as empty as the empty circle, maybe I shouldn’t have won all the marbles.

Tag: drawings

“Weohryant University” (XV) – What 101

Today’s question, said Blurtso, is: “What is that blur of movement?”

I don’t see anything, said Morton.

Neither do I, said Chelsea.

Maybe it’s moving too fast to be seen, said Frank.

I suppose it could be anything, said Morton.

Anything, said Chelsea, that’s moving too fast to be seen.

If it’s moving too fast to be seen, said Emma Lou, how do we know it’s really here?

I suppose we don’t, said Frank.

Maybe we should make a list, said Glouster, of the things that move fast.

I can move fast, said Frank, when I’m hunting or being hunted.

So fast, said Chelsea, that you can’t be seen?

I don’t know, said Frank, I don’t have a mirror.

The next time you’re being hunted, said Chelsea, tell me so I can see if you can be seen.

Humming birds move fast, said Morton.

So fast, said Chelsea, that they can’t be seen?

Yes, said Morton, if you’re not paying attention.

Is it really possible, said Chelsea, for something to move too fast to be seen?

At the subatomic level, said Emma Lou.

That’s because it’s small, said Glouster, not because it’s fast.

It’s both, said Emma Lou.

First we can’t trust our sense of smell, said Morton, and now we can’t trust our sense of sight?

If things can move too fast to be seen, said Chelsea, how do we know we’re not surrounded by things moving too fast to be seen?

I think everything moves too fast, said Morton. Why can’t we all slow down?

That’s a good question, said Emma Lou.

Humans move fast, said Frank.

Yes, said Emma Lou, they’re always in a hurry to get somewhere.

Where do you think they’re going? said Chelsea.

They hurry to work, said Glouster, then hurry to finish, then hurry home, then hurry to go out, then hurry to return.

If something, said Morton, is moving too fast to be seen, is it moving too fast to see?

That’s another good question, said Emma Lou.

People in a hurry can’t see me, said Chelsea.

And the joggers along the Charles, said Glouster, don’t see me.

My cousin, said Frank, was hit by a person who didn’t see him.

I’m sorry, said Chelsea.

What’s the fastest thing in the world? said Morton.

Light is the fastest, said Glouster.

How fast? said Morton.

186,000 miles per second, said Glouster.

That’s fast! said Morton.

So fast, said Glouster, that time stands still.

What? said Morton.

When an object, said Glouster, moves at the speed of light, time stands still for that object.

Who says? said Morton.

Einstein says, said Glouster

The bagel maker? said Morton.

No, said Glouster, the physicist.

So if I moved at the speed of light, said Morton, I’d have all the time in the world?

You’d be immortal, said Emma Lou.

That would be great! said Morton.

Jorge Luis Borges, said Glouster, wrote a story called, “The Immortals.”

What’s it about? said Chelsea.

It’s about a man, said Glouster, who finds the fountain of immortality, takes a drink, and becomes immortal.

Does he move at the speed of light? said Morton.

No, said Glouster, he just lives forever.

Ravens are immortal, said Frank.

They are? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Frank, we can travel from the world of the living to the world of the dead, and back again.

Are you immortal? asked Chelsea.

I will be, said Frank, in the future.

If you could travel at the speed of light, said Morton, you wouldn’t have any future.

What happens to the man in “The Immortals”? said Emma Lou.

He lives for thousands and thousands of years, said Glouster, and learns every language, and reads every book, and does everything again and again and again, until he finally decides to look for the fountain of death.

Of death? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, because immortality is unbearable.

That’s very interesting, said Emma Lou.

It makes you feel sorry for the gods, said Chelsea.

It makes heaven sound less attractive, said Emma Lou.

Maybe moving at the speed of light, said Morton, isn’t so good—you wouldn’t have a future and you wouldn’t have a past, you couldn’t be seen and you couldn’t see.

So death is a good thing? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, it is.

But I don’t want to die, said Chelsea.

Even after you’ve done everything again and again? said Emma Lou.

I haven’t done everything again and again, said Chelsea.

It would be like a “deep and dreamless sleep,” said Morton.

A what? said Chelsea

That’s what the Upanishads say, said Morton.

Are you reading the Upanishads now? said Chelsea. I’m still in the Mahabharata. There’s a war and everyone is fighting for life and death.

I suppose the possibility of death, said Emma Lou, makes life more exciting.

I’m never more alive, said Frank, than when I’m hunting or being hunted.

I still don’t know how, said Morton, moving fast makes time stand still.

I think people move fast, said Chelsea, so that they will have more time.

Time to do what? said Emma Lou.

Time to move faster, said Chelsea, until time stops and they become immortal.

Which is the same as being dead? said Morton.

We’re back to where we started, said Glouster.

I suppose we’ve been moving so fast, said Morton, that we haven’t gone anywhere at all.

“Weohryant University” (XIV)

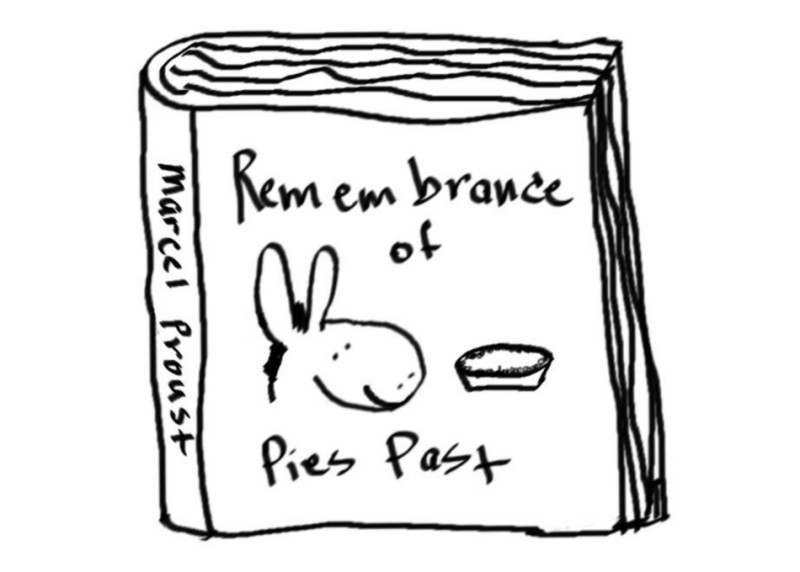

“Blurtso reads Proust”

Mmmm, said Blurtso, taking the first bite of the pumpkin pie he was eating and thinking of all the pumpkin pies he had ever eaten. Mmmm, said Blurtso, taking the second bite of the pumpkin pie he was eating and thinking of all the pumpkin pies he had wanted to eat. Mmmm, said Blurtso, taking the third bite of the pumpkin pie he was eating and thinking of the all the pumpkin pies he was going to eat. Mmmm, said Blurtso, taking the last bite of the pumpkin pie he was eating and wondering where his pumpkin pie had gone while he was eating.

“Blurtso learns to appreciate”

“Blurtso enjoys one of life’s pleasures”

“Blurtso gets an A on his first assignment”

“Weohryant University” (XIII) – Where 101

Welcome, said Harlan, to “Where-101.” Today’s question is: “Where is Borneo?”

What is Borneo? said Morton.

No, said Harlan, “Where is Borneo?”

In Asia, said Glouster.

What’s he doing in Asia? said Morton.

Borneo isn’t a he, said Glouster, it’s an it.

An it? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, an island north of Java.

I like a cup of Java in the morning, said Frank, sometimes two.

Java is an island, said Glouster.

How do you know so much? said Chelsea.

North Borneo, said Glouster, was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1881 to 1941, and a Crown Colony from 1946 to 1963.

Do they speak English in Borneo? said Emma Lou.

The official language is Bahasa Melayu, said Glouster, but English is common, as well as the indigenous languages, Oma Lung and Uma Kulit.

Is Asia far from Boston? said Chelsea.

It’s on the other side of the world, said Glouster.

How far is that? said Chelsea.

Nine thousand two hundred and fifty-two miles, said Glouster.

Wow, said Chelsea, that would take forever!

How fast can you walk? Morton.

Four miles per hour, said Chelsea.

Really? said Morton. I only walk three.

I can fly thirty miles per hour, said Frank.

I wish I could fly, said Chelsea.

I can only walk one mile per hour, said Emma Lou.

I can fly more than forty miles per hour, said Glouster, and swim almost twice as fast.

Wow, said Chelsea, like the speed of light!

Not that fast, said Emma Lou.

Why would anyone live in Borneo, said Morton, if it’s so far from Boston?

Why would anyone live in Boston, said Emma Lou, if it’s so far from Borneo?

What does it feel like to fly? said Chelsea.

It’s like swimming, said Glouster, but in the air.

What does it feel like to swim? said Chelsea.

It’s like flying, said Glouster, but in water.

I don’t swim very fast, said Emma Lou, but I float.

Really? said Chelsea. Without sinking?

Yes, said Emma Lou.

Wow, said Chelsea.

Are there donkeys in Borneo? said Morton.

A few, said Glouster, but there are more elephants.

How many more? said Morton.

Fewer than there were, said Glouster, before their habitat was destroyed.

Is that why you left Borneo? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

That’s very sad, said Chelsea.

Does your family still live there? said Emma Lou.

My brothers, said Harlan, were killed for their tusks.

What?! said Chelsea.

And I don’t know, said Harlan, where my parents are.

I think, said Chelsea, that I’m going to cry.

I’m glad I don’t live in Borneo, said Morton.

It’s a very beautiful place, said Harlan, despite the problems.

Where are your tusks? asked Emma Lou.

I had them removed, said Harlan, so no one would kill me.

Is Asia near India? said Chelsea.

India is in Asia, said Harlan.

Really? said Chelsea. Have you read the Mahabharata?

Yes, said Harlan.

Are you a Hindu? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

Do you believe in reincarnation? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Harlan.

In the Mahabharata, said Chelsea, the god Krishna tells Arjuna all about reincarnation and selfless service.

That part of the novel, said Harlan, is called the “Bhagavad Gita.”

I think there’s an inherent contradiction in the concept of reincarnation and the concept of Atman, said Emma Lou.

A contradiction? said Harlan.

Yes, said Emma Lou. As I understand it, Atman is the universal Brahman as manifested in the individual. Atman is beyond duality—beyond time and space, beyond good and evil, and beyond ego. And being beyond ego it is beyond individuality; it is the undifferentiated “one” that underlies all things. The concept of karma and reincarnation, on the other hand, says that when a person dies the soul returns to become Atman (the undifferentiated “one”), yet this soul somehow retains the karma (unresolved issues) of the individual when that person was living. This soul, with its unresolved issues, must then be reincarnated in the world in order to work through those issues. My question is this: How can the soul, after the death of the individual, become ego-less Atman and yet hang on to the issues of the ego-individual? If the soul becomes “ego-less” after death, it cannot hang on to the unresolved issues of a former ego. Atman and Brahman, by definition, are beyond maya and unresolved issues.

That’s a good question, said Harlan.

What’s the answer? said Emma Lou.

The doctrine of reincarnation, said Harlan, belongs to the apara vidya—or “lower knowledge”—that operates in the world of “maya” or illusion. The Para Vidya—or “Higher Knowledge”—removes the illusion of the manifold world and, with it, the illusion of the individual soul and its birth, death and hereafter. The function of organized religion is twofold. On one hand it teaches the secrets of wonder and mystery, and on the other it is a rule book for a functioning society. For those with Para Vidya, those who can truly understand the “oneness” of all things, there is no need for the concept of reincarnation, because there are no unresolved issues in “oneness.” For those who cannot embrace or “experience” the mystical union that is beyond individual objects, karma and reincarnation play a civilizing role. They inspire members of society to perform “good” rather than “evil” deeds. They function the same way as heaven and hell in the Biblical tradition—the “carrot and stick” that encourage individuals to behave in a civilized manner without acting like barbarians and killing each other.

Do you, said Emma Lou, have “Higher Knowledge” and embrace the mystical union beyond individual objects?

Yes, said Harlan, I believe I do.

Then why do you believe in reincarnation?

I believe in reincarnation, said Harlan, as a civilizing force for those who remain tied to the illusion of individual objects. I don’t not believe in reincarnation for myself.

“Weohryant University” (XII) – When 101

“Weohryant University” (XI) – What 101

Welcome, said Blurtso, to “What 101.” The question for today’s class is: “What’s that smell?”

What’s that smell? said Glouster.

I didn’t do it, said Emma Lou.

I don’t smell anything, said Frank.

I do, said Morton.

So do I, said Chelsea, it smells like jasmine.

It also smells like pumpernickel, said Morton, or a field of wheat before it rains.

Yes, said Chelsea, or a riverbed of Alabama clay.

I don’t smell anything, said Frank.

You can’t trust your senses, said Glouster, everyone has a different sense of smell.

That’s what the Upanishads say, said Emma Lou.

The Upanishads? said Morton.

Yes, said Emma Lou, the Upanishads say that the world perceived by the senses is maya.

Maya? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Emma Lou, separate smells and sights and things only exist as the condition of perception. They are an illusion. At the subatomic level they dissolve into a flux of energy.

Does an odor exist, said Frank, if you can’t smell it?

Does an odor exist, said Emma Lou, if you can smell it?

Maybe, said Glouster, we should consult Avery Gilbert’s book, The Science of Scent in Everyday Life. Or Patrick Suskind’s novel, Perfume.

Perfume? said Morton.

Yes, said Glouster, a novel about the emotional meanings that scents carry. The protagonist is a perfume-maker in 18th century France.

I love perfume, said Chelsea.

I can’t smell perfume, said Frank.

There’s another novel about smell, said Glouster, in which a man takes a bite of a cookie that makes him remember his childhood and the life he’s lived.

What’s it called? said Emma Lou.

Á la recherche du temps perdu, said Glouster, by Marcel Proust.

What kind of cookie does he eat? said Morton.

A Madeleine, said Glouster.

What’s a Madeleine? said Morton.

A Madeleine, said Glouster, is a buttery sponge cake.

I love sponge cake! said Chelsea. Why can’t we read a book about sponge cake instead of the Bible and the Quran and the Upanishads?

There’s a donkey in the Bible, said Morton.

There is? said Chelsea.

Yes, said Morton, Jesus entered Jerusalem on a donkey.

There are donkeys in the Quran too, said Glouster.

There are? said Chelsea.

I still don’t smell anything, said Frank.

I do, said Chelsea, it smells like something sweet.

Maybe Bonny is baking a pie! said Morton.

No, said Glouster, that’s only on Thursdays.

If we can’t trust our senses, said Chelsea, what can we trust?

“To smell,” said Glouster, is “to perceive the scent of something by means of the olfactory nerves.”

Isn’t that circular, said Emma Lou, to say, “to smell is to perceive scent”? It doesn’t explain anything.

If you smell something before you eat it, said Morton, it gives you an idea of what it’s going to taste like.

Sponge cake smells sweet, said Chelsea.

So do chocolate chip cookies, said Morton.

I’ve never had a chocolate chip cookie, said Frank. What do they taste like?

It’s hard to describe, said Morton, to someone who has never tried one.

“To taste,” said Glouster, is “to ascertain the flavor of something by taking a little into the mouth.”

That doesn’t tell me what it tastes like, said Frank. Does it taste like a worm?

A worm? said Morton. I don’t know, I’ve never tasted a worm.

Does everything, said Chelsea, taste different to everyone?

That’s a good question, said Frank.

Did anyone bring cookies? said Morton.

“The senses,” said Glouster, are “the physiological capacities of organisms that provide data for perception.”

Data for perception? said Frank. Does that mean we don’t actually perceive things themselves, we only perceive data?

Every time I perceive the data called smoke, said Morton, it reminds me of when I was tethered in a barn and the barn caught fire and someone rushed in to save me before I was burned alive.

That must have been terrifying! said Emma Lou.

Every time I perceive the data called smoke, said Chelsea, it reminds me of roasted chestnuts on the Mass. Ave Bridge.

“Harvard Bridge?” said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, in December.

From a man in a green overcoat? said Morton.

Yes, said Chelsea, and on Saturdays he brings his daughter.

Those are excellent chestnuts, said Morton.

But you can’t eat them at once, said Chelsea, because they’re too hot, so you have to wait, but you can’t wait, so you eat them and they burn your tongue.

The data burns your tongue, said Morton.

When I perceive the data called smoke, said Frank, I fly in the opposite direction.

I dive underwater, said Glouster.

Really? said Chelsea. I wish I could swim.

You can’t swim? said Glouster.

No, said Chelsea, I don’t think so.

It’s easy, said Glouster, you just paddle around, and then dive down when you see something to eat.

Like what? said Chelsea.

Like a fish, said Glouster.

I couldn’t catch a fish, said Morton.

Neither could I, said Chelsea.

Some animals are not fishers, said Frank.

The Apostles of Jesus, said Glouster, were fishers of men.

Fishers of men? said Emma Lou.

Yes, said Glouster, they used the holy word of God to entice people to open their hearts and love their neighbors.

Just like in the Upanishads, said Emma Lou.

Is that in the Bible? said Chelsea. I’ve been reading the Mahabharata. It starts with a story about a girl who is turned into a fish. And then she has children that smell like fish.

Even I can smell a fish, said Frank.

Then a wise man called a “rishi”, said Chelsea, becomes obsessed with the girl’s smell and makes love to her.

I don’t like the smell of fish, said Morton.

What smells bad for one person, said Emma Lou, smells good for another.

Fish must like the smell of fish, said Chelsea.

They sure do taste good, said Glouster.

Yes, said Frank, especially when they’ve been baking in the sun for a while, on the side of the road, or in a ditch near a field.

I’m sorry to interrupt, said Blurtso, but we’re out of time. I hope you enjoyed the first day of class. Thank you for your interesting comments and questions.

Thank you, said Emma Lou, you’re an excellent teacher.