I guess I should be bored in this field, thought Blurtso. I guess I should be restless and anxious and troubled. I guess I should be worried about the things I’m missing, all the excitement taking place without me. I guess I should be depressed. I guess I should feel that standing in this field is the worst thing in the world. Yes, thought Blurtso, that’s what I should feel…

Category: Corporate destruction

“Blurtso considers ambition”

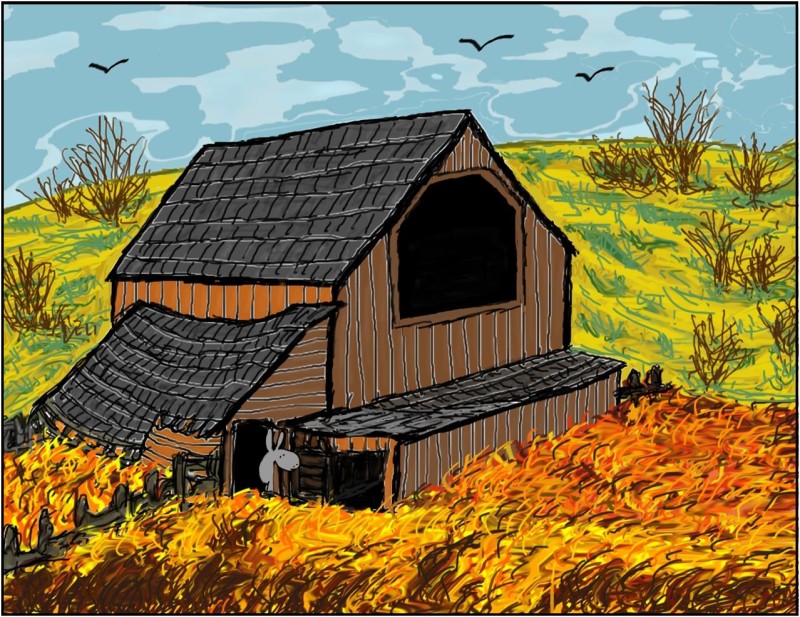

“Blurtso finds an abandoned barn”

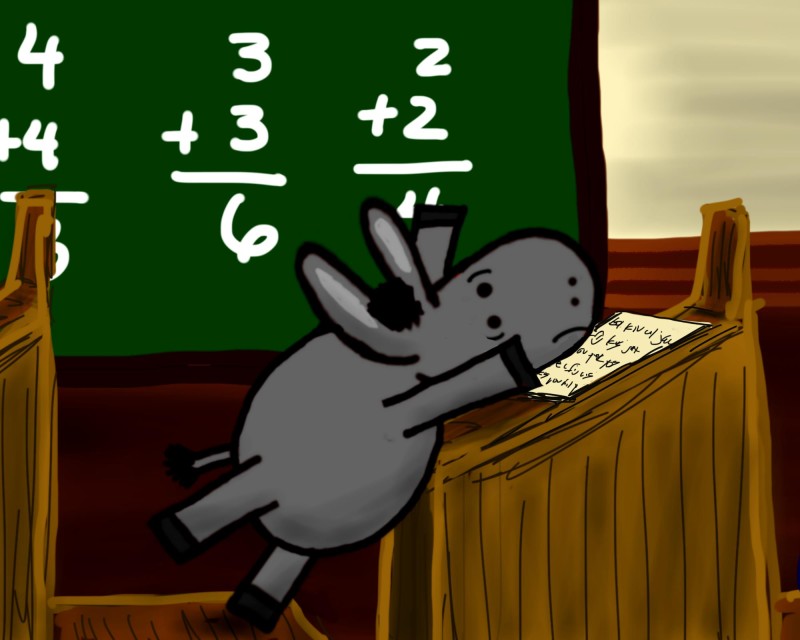

“Ditto goes to school” (XXVII)

I’m going to say two words, said the schoolmarm, tell me which begins with “eh.” Listen carefully: egg, pan. Which word begins with “eh”? Egg begins with “eh.” Now, I’m going to say two more words. Tell me which begins with “h”… I wonder, thought Virginia, what Ditto is thinking? It looks like he’s paying attention. I never realized how boring this class was until I got put in intervention. We never say what we think. We just repeat. I wonder if the schoolmarm likes what she does? I guess grown-ups don’t get bored as easy as kids.

“Blurtso considers the elimination of humans”

Why do humans, said Blurtso, interfere with nature? Humans, said Pablo, are creatures of nature, and as creatures of nature they inevitably act naturally, so their conscious interference in nature must be working in the interests of nature, even if that interference turns out to be nature’s way of eliminating humans.

“Ditto goes to school” (XXI)

Hello, said Ms. Johnson, I’m Ms. Johnson. Hello, said Ditto, I’m Ditto. Nice to meet you, Ditto. Nice to meet you, Ms. Johnson. I understand, said Ms. Johnson, that you had some trouble with the Dibels test. Yes, said Ditto, the words didn’t make any sense. Didn’t the schoolmarm explain, said Ms. Johnson, that the words were make-believe words? Yes, said Ditto, but even make-believe words have meaning. I don’t understand, said Ms. Johnson. Aren’t all words, said Ditto, make-believe words? All words? said Ms. Johnson. Yes, said Ditto, the word “tree” has no ontological relationship to the thing we call a tree. We might invent any word and make believe it refers to a tree. In fact, that’s what we’ve done since the beginning of language—the word for tree is different in every language that exists—all the different words are simply make-believe words that we’ve agreed upon to refer to trees.

You’re exactly right, said Ms. Johnson. And if someone is asked to read a group of make-believe words, said Ditto, how do they know that the words don’t have make-believe pronunciations? They don’t know, said Ms. Johnson, because the group of make-believe words might constitute a make-believe language, with its own grammar, syntax, and pronunciation. Exactly, said Ditto, that’s why I had trouble with the test. Would it have helped, said Ms. Johnson, if the schoolmarm had said the words were “meaningless”? Meaningless? said Ditto. How could they be called meaningless if they’ve determined where I have to spend my lunch hour? Yes, said Ms. Johnson, the two of us are going to get along very, very well.

“Ditto goes to school” (XIX)

An abject failiure? said Virginia. Yes, said Ditto, that’s what the teacher called me. I’ve never heard the word “abject”, said Virginia. “Abject”, said Ditto, refers to someone cast down in spirit, someone reduced to hopelessness and surrender. Really? said Virginia. Yes, said Ditto, at least that’s the way Thoreau uses it. Thoreau? said Virginia. Henry David Thoreau, said Ditto, a man who wrote a book called Walden—my parents have a copy and they let me read it. Was Thoreau abject? said Virginia. No, said Ditto, but near the end of the book when he’s talking about the importance of protecting your thoughts he says, “Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts… if I were confined to a corner of a garret all my days, like a spider, the world would be just as large to me while I had my thoughts… from an army of three divisions one can take away its general, and put it in disorder, but from the man the most abject and vulgar one cannot take away his thought.” How come you can read Walden, said Virginia, but can’t pass the Dibels? I don’t know, said Ditto, I guess Walden is a different kind of reading, or maybe Thoreau has been outlawed.

“Ditto goes to school” (XVIII)

It’s your turn, said Virginia, I’m sure you’ll do fine.

Alright big-nose, said the schoolmarm, you’ve got sixty seconds.

Read as many words as fast as you can… Begin!

DIBELS Nonsense Word Fluency

bol kiv ul jac lel

fij kug jat oj deg

wav pek yos mub fiv

ec faj vog kif puk

“bol?” said Ditto, What’s a “bol?” Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. But “bol” isn’t a word. Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. But it doesn’t make sense. Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. But there aren’t any words. Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. This isn’t English, said Ditto. Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. Can I use a Rosetta stone? Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. Or the Pentagon’s decoding program? Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. Or maybe a soothsayer? Just read the word, said the schoolmarm. Or a deck of Tarot cards? Stop! said the schoolmarm. Your time’s up! You scored one out of forty, you’re a red light. A red light? said Ditto. Yes, said the schoolmarm, an abject failure, you’ll start intervention in the morning.

“Ditto goes to school” (XVII)

Will they kick me out of school, said Ditto, if I fail the Dibels test? No, said Virginia, they’ll put you in an intervention class an hour a day until you pass the test. What if I never pass? Then you’ll be in intervention forever, said Virginia. Isn’t there any way, said Ditto, I can get kicked out of school?